Remembering 9/11

Where the South and North towers of the World Trade Center used to stand, there is now a reflecting pool surrounded by a wall that bears the name of each of the victims.

Twenty years ago, the most devastating attacks to take place on American soil since Pearl Harbor united the country and much of the world in shared shock, anger, and grief. Unlike so many of the countless tragedies that come and go on the nightly news with alarming regularity, 9/11 was a tragedy that touched nearly everyone and then sat like a stone in the pit of our stomachs every time we thought about it or were reminded of it. It was a shared horror that millions of us endured together in real-time as we watched the 24 hour news coverage for days on end. It was a shared tragedy that changed how many of us see the world forever.

For everyone old enough to remember 9/11, there is a personal story. Mine is the story of a person who at that time lived a one hour train ride from New York City, traveled frequently to the city on business, and who was fortunate enough not to be in the city on that fateful day. Like many people who spent time in the area both before and after the attacks, my 9/11 experience started well before September 11, 2001 and continued for many years afterwards.

A few years ago, my wife, Kim, and I took a bus ride from our adopted city of Portsmouth, New Hampshire to New York City. It was 2014 and the weekend before Thanksgiving. Our goals were to do a little early shopping for the holiday, to revisit some old haunts, and to see the 9/11 Memorial Museum which had recently opened.

It was a visit that brought back many memories—some good, others horrific.

Over the years, I’d visited lower Manhattan frequently to call on clients in the financial district. Over time, like many out-of-towners, I became familiar with the streets and subway routes. On weekends, we’d often make family trips into the city. One weekend in 1995, Kim had planned a trip into the city with her mom to see “The Sunshine Boys” with Jack Lemon and Walter Matthau. I tagged along with my son, Justin, who at the time was a fidgety 7-year old with zero interest in Broadway shows, but who was completely enthralled by tall buildings. With the Empire State Building already scratched off his list (several times by that point) we left Kim and her mom at the theater on Broadway, jumped onto the subway, and headed for the World Trade Center. After a long ride filled with multiple inquiries of “are we there yet?”, we found ourselves at the World Trade Center subway station—an underground marvel that, to me, always looked more like a high-end shopping mall than a subway station.

I remember how excited he was as we made our way outdoors and onto the courtyard. We walked right up to the nearest tower and I had him lie down and close his eyes. Then I positioned his feet against the building and told him “OK…now open your eyes.” He opened them and screamed with delight (at least I’ve always hoped it was delight) as he experienced a whopping dose of vertigo.

After likely traumatizing the poor kid for life, we made our way past the big golden globe, paid the fee, and took the elevator to the top. When we got there, I told him the story of Philippe Petit—the daredevil who once tightrope-walked between the two towers. We stayed up there for at least half an hour, looking at the city from every angle, pointing out landmarks like the Statue of Liberty and Newark Airport, wondering what it would be like to have lunch at Windows on the World, and trying to figure out how Philippe managed not to fall.

When we got down, we had lunch at a place nearby that somehow survived the 9/11 attacks, but not the exodus of Lower Manhattan workers when the 2020 pandemic forced most to work from home.

My final visit to the WTC complex was three days before the attacks on Friday September 8, 2001. Like the day of 9/11 itself, it was clear, crisp, and cloudless. Our meeting in the adjacent Deutsche Bank building started at about 3pm and went well after 6pm. After it was over, I remember walking across the plaza as the light faded and noting the incredible beauty of the towers, all lit up against a colorful but fading sky.

Three days later, I was in my office at Hewitt Associates in Connecticut getting ready for a big meeting. When I arrived that morning, dozens of out-of-town coworkers were already there. Most had flown in the night before, but many others were flying in that morning from places like Atlanta and Chicago. Suddenly, a friend rushed into my office to tell me she heard a plane had just hit the World Trade Center. I remember thinking it was probably a Cessna and went back to my prep work. Then the first reports started appearing online. Not a Cessna, but a passenger plane—a big one. One of the towers had smoke pouring out of it. I remember thinking what a terrible accident it was and wondered how a passenger plane could have veered that far off-course.

Within minutes, we knew it was no accident when another plane hit the second tower. Immediately, we canceled the meeting and started checking to see if all of the people who were supposed to be attending had arrived safely.

Knowing that no more work was going to get done that day, many of us crowded into the largest conference room in the building, where someone had wheeled in and hooked up a 27” TV.

As we watched, most people were busy on their cell phones. Keep in mind, those were the pre-iPhone days when your cell phone was good for making phone calls, but not much so much for text messaging or following events online. Some were quietly trying to reach relatives working in the financial district, while others were letting their own families know they had made it safely from the airport to the office. One group of colleagues arriving later in the morning told of driving away from Laguardia airport in their rental car when they saw smoke and fire behind them in their rear view mirror as the towers burned. (Fortunately, in the end, everyone arrived safely and none of our coworkers were in either of the airplanes involved in the attacks. But years later, after our company merged with another consulting firm, we learned that 176 former Aon colleagues had been killed in the attacks.)

We had just started to watch the news coverage in the conference room when we heard that a third plane had hit the Pentagon. We were all looking back and forth between the TV and each other in shock as we realized this was bigger than the attack on New York. Not long afterwards, the first tower suddenly collapsed—something none of the newscasters or any of us watching in horror thought was even possible. It was followed by the stunning collapse of the second tower half an hour later. I remember some of my colleagues starting to cry and others filtering out of the room to go back to their offices, pack up their stuff, and go home to be with their families. Not long after that, the first reports started to filter in about Flight 93 crashing over Pennsylvania.

At that point I remember being in a state of shock myself. I left the conference room and joined coworkers who were quietly milling around in small groups to try to digest what it all meant. Many were also still trying to figure out if friends, relatives, and clients in the city were safe. But on that day no one was getting through to anyone in New York City who was using a cell phone. As it turned out, the largest cell phone tower in Lower Manhattan had been on the roof of one of the collapsed towers.

Meanwhile, those who had flown in for the meeting soon faced another problem—how to get home after the “no-fly” order was issued. (One group wound up renting a passenger van and had a bonding experience driving back to Chicago—all the way trying to digest the events we all knew would change us forever).

The next week I learned the client I had met with on September 8 had been in her office when plane parts—including an entire jet engine—slammed into and through the windows of her building, including those of the office we met in three days before, injuring her and killing some of her coworkers.

A few weeks after that, when the trains were running again, I made my first trip back into the city. Even in Central Manhattan near Grand Central Station and miles away from Ground Zero, the smell of smoke and debris remained strong. But the most heartbreaking thing of all was seeing the thousands of posters plastered all over the station and all over the city, most starting with the words “Missing” or “Have You Seen…”.

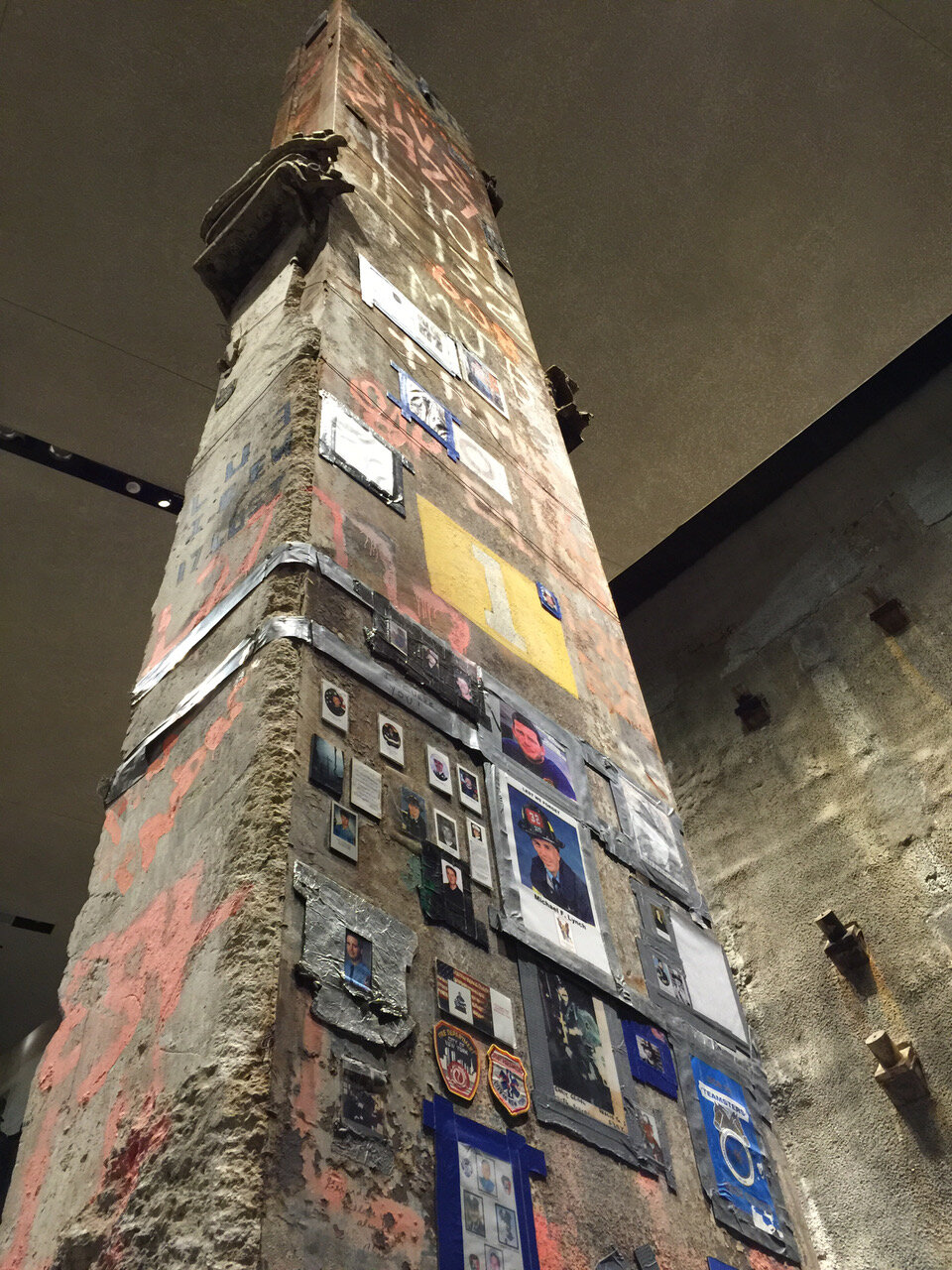

Like the first responders and the survivors we saw on television, the faces on these hand-made posters became the faces of 9/11–each one symbolizing a mixture of desperate hope and, eventually, incomprehensible loss. While a few of the missing people eventually turned up, the vast majority were never found or heard from again. The 9/11 Memorial Museum has several areas where many of the posters and shrines to the victims are now displayed after having been carefully saved by employees of the city. By 2014 when I saw them again, some had started to fade with the progress of time.

Not long after my first visit to the city after 9/11, I had a meeting with a company in New Jersey on the other side of the East River. When we got to the conference room, we saw it had a spectacular view of Manhattan—including the World Trade Center site, which was still smoking. Before the meeting started, I asked one of our clients if she’d been at work the morning of the attacks. She nodded slowly and sadly and put down her charts and handouts.

We both looked across the river in silence.

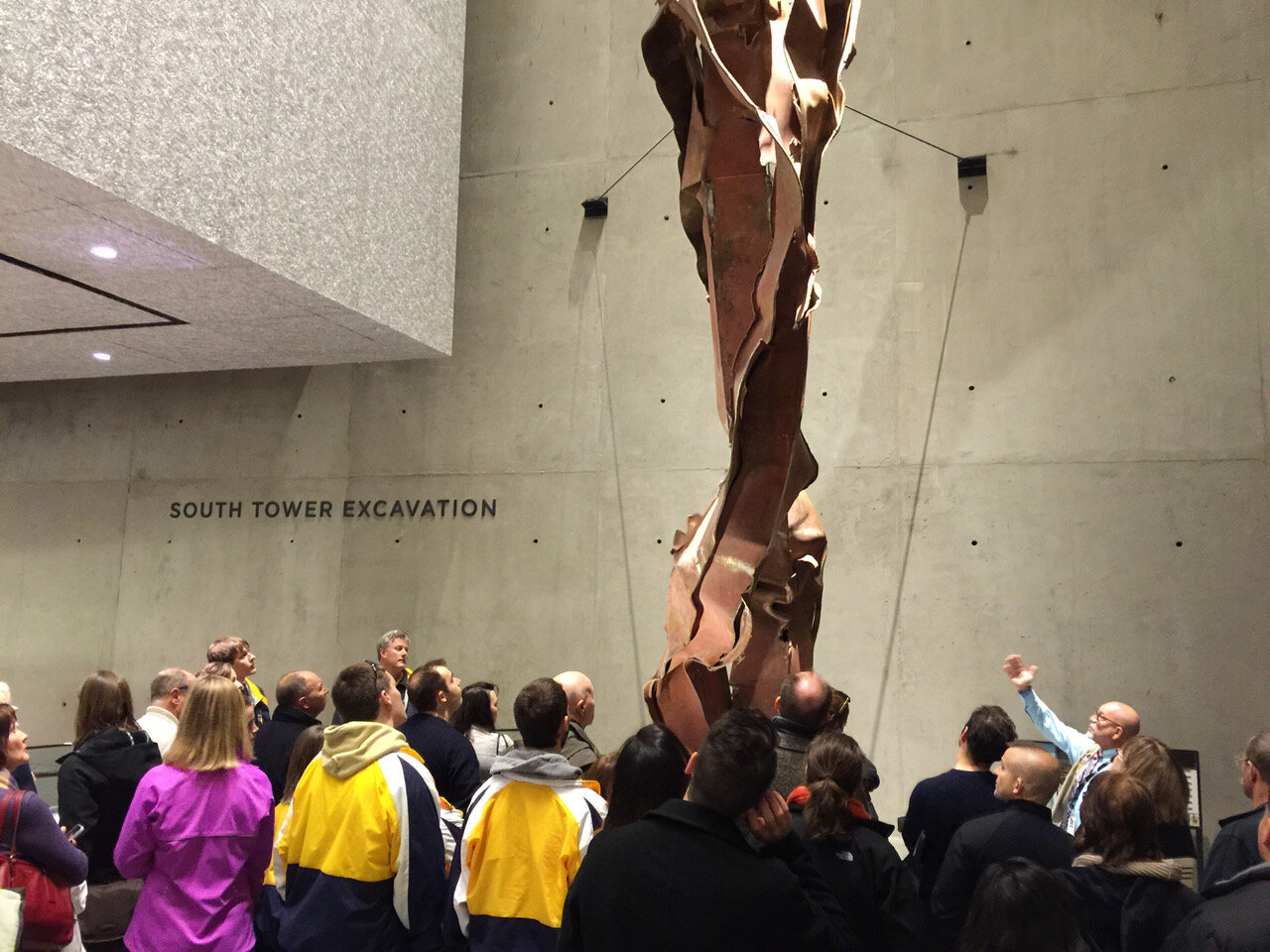

Eventually, Lower Manhattan started to open up again. The debris was hauled out of the streets and over time, what had been a giant pile of twisted steel and rubble instead became a giant hole in the city itself. In many ways it symbolized the even larger hole left behind by the many victims. Most of the rubble went to landfills in New Jersey. Some of the steel would eventually find a home in what would become the 9/11 Memorial Museum. Other pieces gradually made their way to cities across the country for local 9/11 memorials. In Portsmouth, the city erected a memorial that displays part of a beam from one of the towers outside City Hall and police station. A Portsmouth resident, Tom McGuinness, was the co-pilot of American Airlines Flight 11, the first plane flown into the towers.

Many months later after the attacks, I remember emerging from the newly reopened Wall Street Station and looking up. Where the towers used to dominate the landscape, there was nothing but empty sky. It was shocking and unsettling to see such a familiar sight look so strangely different.

Revisiting the same area 13 years later with Kim was in some ways similar to visits we’ve made to places like the American Cemetery near the D-Day beaches in France, Gettysburg, Pearl Harbor, and Boston’s Holocaust Memorial. What was different was that in all of those other places we felt like respectful tourists, honoring the dead and trying to better understand their sacrifices and their stories. But 9/11 was different in one very important way. It was our story too—something we had witnessed that we were fortunate to have escaped ourselves, but that became indelibly imprinted on our memories.

Today, the old World Trade Center site looks very different and the hole in the ground is long gone. In its place is the above-ground entrance to the largely underground 9/11 Memorial Museum. A giant reflecting pool covers the original footprint of the towers. The pool is surrounded by a short granite wall polished to a shine and engraved with the names of each the victims. The wall is dotted with white roses placed there in memory of the people who didn’t survive. In the background, the new Freedom Tower rises defiantly—a mammoth and beautiful building soaring high into the sky that despite its majesty somehow still fails to fill the emptiness and the sense of loss you feel as you read the names on the wall and gaze across the pool.

Below ground-level inside the 9/11 Memorial Museum there is a giant concrete wall that separates visitors from a repository holding the unidentified remains of victims of the attacks. It features a quote of Virgil’s: “No day shall erase you from the memory of time.” The words stretch for 60 feet and dominate the wall.

It is a solemn, fitting, and timeless way to express a sentiment shared by every American who lived through that terrible day.

We will always remember.

We will never forget.

No day shall erase you from the memory of time.